| NSPM in English | |||

Remembering Mihajlo Mihajlov |

|

|

|

| среда, 07. март 2012. | |

|

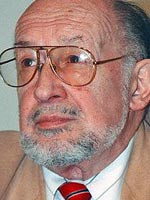

I noticed that Mihajlo Mihajlov’s detention raised difficult questions even for the so-called average Yugoslav citizen who would otherwise choose to ignore politics. What kind of society did we have if we imprisoned an intellectual who fought for peaceful democratic change? Why was he not allowed publicly to defend himself from attacks in the press? Should I not do something? Of course, the last question raised feelings of guilt, and caused discomfort, even pain, so that more often than not, the answers were angry comments about Mihajlov. Today I would say that dissidents made a huge contribution to ending the one-party government system in Eastern Europe by instilling creative distress and anxiety within people’s consciousness and conscience. And this included people in power. Even if some did not want and others were not able to end Mihajlov’s imprisonment, he remained entirely devoted to the ideals of freedom, democracy and the rule of law. Tito’s régime granted him amnesty in November of 1977 (the date of Mihajlov’s final release from prison) because Belgrade was the host town of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, during which, amongst other things, issues relating to human rights were to be discussed. Mihajlov’s comment was: Yugoslavia is really not a country with rule of law – first they sentenced me without legal basis, and now they have granted me amnesty before I have completed half of my sentence, though the law does not allow such early release! Forgetting oneself… Only much later did I become aware of how deeply this quality resided in Misha spirit. Not only did he never fight for power, but he could not have been more indifferent to rank, title, or career. When he left for the West in 1978, he had worldwide renown. Andrei Sakharov nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize, Malcolm Muggeridge, a leading British publicist, proclaimed the collection of essays that he authored, Unscientific Thoughts, to be the book of the year, Prince Charles sent him a handwritten letter, and politicians, artists and distinguished intellectuals wanted to meet him. However, even though he was teaching Russian literature and philosophy at prestigious American universities, Misha devoted most of his energy and time to activities from which he gained no personal benefit – he wrote political articles and gave interviews, initiated actions that would help dissidents in Yugoslavia and Eastern Europe, created committees for democracy in Yugoslavia and worldwide, and engaged in polemics with Yugoslav and Russian émigrés. Misha showed no concern for his well-being. He did not eat regularly, nor did he care if the food he ate was healthy. He slept little, he visited the doctor only on rare occasions, he often did not dress warmly. He could have lived anywhere he wanted – in America, in European capitals, in Moscow – but he chose to return to our country and to end his days in a tiny apartment in Belgrade. And he was never bitter that our society did not bestow upon him the honors he undoubtedly deserved. Because of his belief that his fight for democracy was assigned to him by a divine force (Misha was very religious), and that his dissident mission had global significance, some people perceived him as conceited and indeed as a megalomaniac. However, he was much less vain than most men of letters I knew. His knowledge of literature was huge. He read much religious philosophy, as well as critiques of Marx and Lenin. From the field of political theory, he knew well the main treaties relating to freedom and tyranny. Yet his knowledge was not bookish. It completely permeated his life and his dissident work. He constantly inhabited a world of art and faith, and carried with him a strong feeling that the ideas with which he was imbued originated from some higher reality. Very soon after I first met him, I discovered that Misha was given to a boyish love of harmless tricks and practical jokes. Even though he was my senior by almost two decades, he often seemed younger and somehow even ageless. I retained that impression of him for the rest of his life. His personality had additional contrasts. Nobody would assume that this rather short, plump guy ever knew more about physical effort than how to take a book from a book-shelf, but in fact, in his youth he was a successful gymnast. At the age of forty he could still do a one-hand head-stand. He was also a skilful spear-fisherman, a terror for dusky grouper in the Zadar bay area. As a nervous and impatient person, he was always in a hurry, but at the same time he was ready to be engaged in a struggle that he knew was likely to last (and did last) for decades. An uncompromising fighter for democracy, he fully accepted his destiny as a dissident, convict and émigré. His manners were old-fashioned – he was a gentleman of the nineteenth century – but, at the same time, he could become short-tempered and get angry. He was even prone to misunderstanding or misinterpreting things that were said or written with good intention, and then to reacting too critically. However, I never felt that he carried hatred or desired revenge. He did not hold grudges. He and I collaborated mostly in the eighties, when I was a political émigré in London and wrote for Our Word, a Serbian monthly journal edited by Desimir Tosic. Collaboration with Misha was not easy, but it was fruitful. One of the proofs was Dr. Obren Djordjevic’s attack on us in May of 1982 – he was the head of Serbian UDBA – when he alleged we were extreme émigrés and destroyers of the constitutional order. Mihajlo Mihajlov's faith in the power of words had no limits. He did his utmost to attract everyone for democratic and humanistic ideas. And he was always sincere – not only did he not say what he did not think, but I am also convinced that he never thought about something without immediately saying it. Many émigré groups, both Serbian and Croatian, liked his criticism of the Titoistic one-party régime, but they did not like his championing of non-violent methods and his opposition to any kind of nationalism. Yet Misha made a great effort to impress upon extreme nationalists and fanatical anti-communists, who desired a second round of civil war, his humanistic ideals based on good for all people. Even though the results were modest, they did not diminish his enthusiasm. In 1983, in London, Vane Ivanovic and I prepared and published an Almanac on Human Rights. As our audience, we had in mind primarily the people of a growing opposition movement in Yugoslavia. Misha submitted to it his “Pieces of Advice to a Political Prisoner”, an article that was both useful and wise, based on his rich personal experience with police, trials and prisons. In this article he wrote: “A lonely man surrenders more easily.” Very true, but not if his name was Mihajlo Mihajlov! Once again Misha had forgotten himself while thinking of others. |

Остали чланци у рубрици

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Из архиве - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

.jpg)

I met Mihajlo Mihajlov long ago, in 1970, soon after he had been released from prison. It was neither his first, nor last, detention – the total time he spent in jail was seven years. I was a high school student at that time, but I felt as if I had already known him well because he was so often a topic of conversation in our household and amongst our friends. My father, Milovan Djilas, wrote a letter to Tito on March 20, 1967, less than three months after he himself was released from prison, in which he asked for this “young man and talented writer” also to be freed from jail.

I met Mihajlo Mihajlov long ago, in 1970, soon after he had been released from prison. It was neither his first, nor last, detention – the total time he spent in jail was seven years. I was a high school student at that time, but I felt as if I had already known him well because he was so often a topic of conversation in our household and amongst our friends. My father, Milovan Djilas, wrote a letter to Tito on March 20, 1967, less than three months after he himself was released from prison, in which he asked for this “young man and talented writer” also to be freed from jail.